There exists a peculiar pilgrimage undertaken by serious watch collectors, one that has nothing to do with boutique openings or manufacture tours. It leads instead to a tower erected in 1218—27 years after the founding of Bern in 1191—by Duke Berchtold V of Zähringen. Here, in this structure that predates Swiss watchmaking by centuries, a clock has been marking time since 1530—nearly three centuries before the first Vacheron Constantin left the atelier of Jean-Marc Vacheron.

If you ever find yourself in Bern, this is a must-see. The best part is that it cannot be missed as it sits in the center of Old Town Bern and is an unmistakable landmark, located just steps away from the Einsteinhaus on Kramgasse 49, where Albert Einstein lived between 1903 and 1905.

The Zytglogge commands the Kramgasse—main street in the Old City of Bern—with an authority no modern timepiece could match. Its massive astronomical dial, rendered in black and gold, dominates the tower's western face, while below it, an astrological calendar tracks the zodiac's procession with medieval precision.

The tower itself tells Switzerland's story. Erected as Duke Berchtold's guard tower in 1218, transformed into a civic timekeeper in 1530, restored in 1770 as commemorated by the Latin plaque in black marble beneath its dial, and maintained through subsequent centuries, it embodies the Swiss approach to watchmaking: respect for tradition coupled with practical evolution. Nothing is discarded that still functions; everything is maintained with exacting care. The recent restoration work, completed with traditional materials and techniques, demonstrates Switzerland's commitment to preserving horological heritage.

But statistics and dates fail to capture what one experiences standing beneath this monument: the overwhelming sense that Swiss watchmaking didn't emerge from valleys and ateliers, but from this single mechanical heart beating at the center of the old capital.

Kaspar Brunner's 1530 movement represents something beyond mere timekeeping. This is mechanical philosophy made manifest—an attempt to capture not just hours and minutes, but humanity's relationship with celestial order. The astronomical complications track the sun's position along the ecliptic, moon phases cycle through their eternal rhythm, and the zodiac rotates with patient inevitability. One recognizes in these functions the DNA of every grand complication that would follow: the perpetual calendars, the astronomical displays, the cosmographic interpretations that define haute horlogerie's highest achievements, much like the principles behind watches like the Patek Philippe Celestial ref. 6102 or the Vacheron Constantin Les Cabinotiers Solaria Grande Complication.

The movement itself operates on principles that remain foundational to modern watchmaking: weight-driven power delivery, verge escapement regulation, and gear train calculation that must account for celestial mathematics. Standing in the tower during guided tours—offered daily and highly recommended—one encounters an exceptional museum installation that chronicles the tower's evolution from Duke Berchtold's 1218 defensive fortification through its transformation into the city's mechanical timekeeper.

The automaton’s performance, triggered each hour, deserves particular attention from the horologically inclined. Precisely four minutes before the hour, the mechanical pageant begins: Chronos—the God of Time— strikes his bell, the procession of bears parades, and the golden rooster crowns thrice.

This isn't entertainment—it's a demonstration of mechanical programming that predates computer science by four centuries. The sequential triggering of multiple independent mechanisms, all synchronized to a master clock train, represents engineering sophistication that would challenge many contemporary watchmakers.

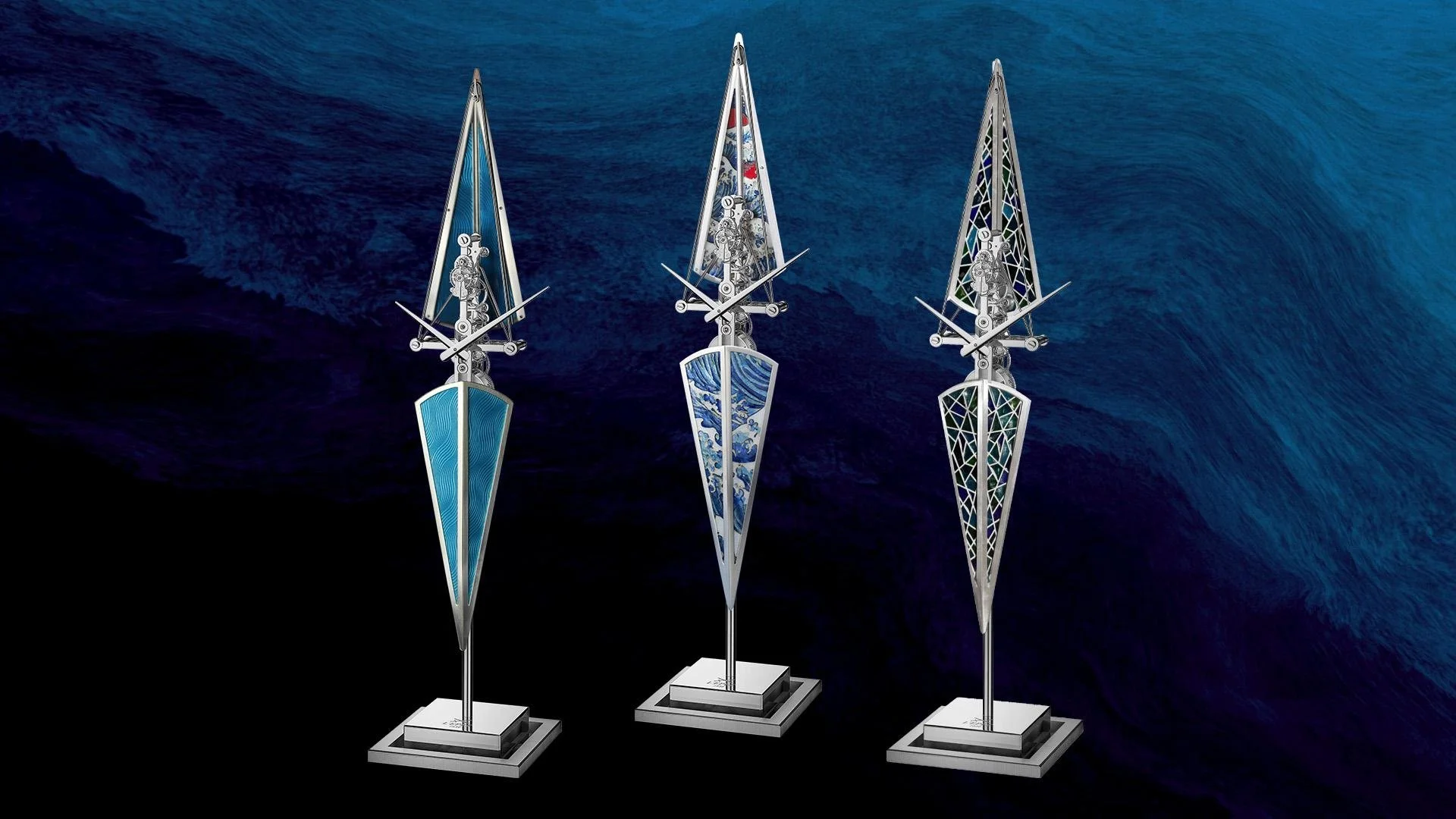

What strikes the informed observer is continuity. The complications celebrated in today's seven-figure timepieces—astronomical indications, automata, calendar functions—all trace their lineage to public clocks like the Zytglogge. When Vacheron Constantin interprets astronomical functions with a watch like the Métiers d’Art Copernicus Celestial Spheres or the Celestia Astronomical Grand Complication ref. 3600, when any independent watchmaker masters perpetual calendar mechanics like the De Bethune DB Kind of Grande Complication, they're engaging with horological language first codified here, in stone and bronze and massive wheels. The new Vacheron Constantin La Quête du Temps Mécanique d'Art Clock is a perfect example of astronomical indications.

For the traveling collector, the Zytglogge offers something no boutique or manufacture visit provides: perspective. Standing in the Kramgasse as the mechanism initiates its hourly ritual, watching non-watch nerd tourists photograph what they don't quite understand, one grasps an essential truth.

The 40 mm complications we obsess over, the movements we study through sapphire case backs, the complications we debate and acquire—all of it descends from this. Swiss watchmaking's soul doesn't reside in corporate headquarters or even in the manufactures of the Vallée de Joux. It beats here, in Duke Berchtold's medieval tower, marking time as it has for half a millennium, mechanical and eternal and profoundly Swiss.